Written by Astrid Naranjo (Clean Health Accredited Clinical Dietitian)

What are nutrients?

What is an essential nutrient?

What is dietary fiber and where does it fit within these definitions?

Well, nutrients, on the one hand, are substances in food that provide structural or functional components or energy to the body, whereas an essential nutrient is a substance that must be obtained from the diet because the body cannot make it in sufficient quantities for growth and development and/or the maintenance of life (1,2).

On the other hand, dietary fiber, is defined ‘the edible parts of plants or analogous carbohydrates that are resistant to digestion and absorption in the human small intestine with complete or partial fermentation in the large intestine’ (4,5).

So, although it does not meet the criteria of being needed for life/growth, hence theoretically speaking, not considered an essential nutrient, fiber is undoubtedly an essential part of a healthy diet (3).

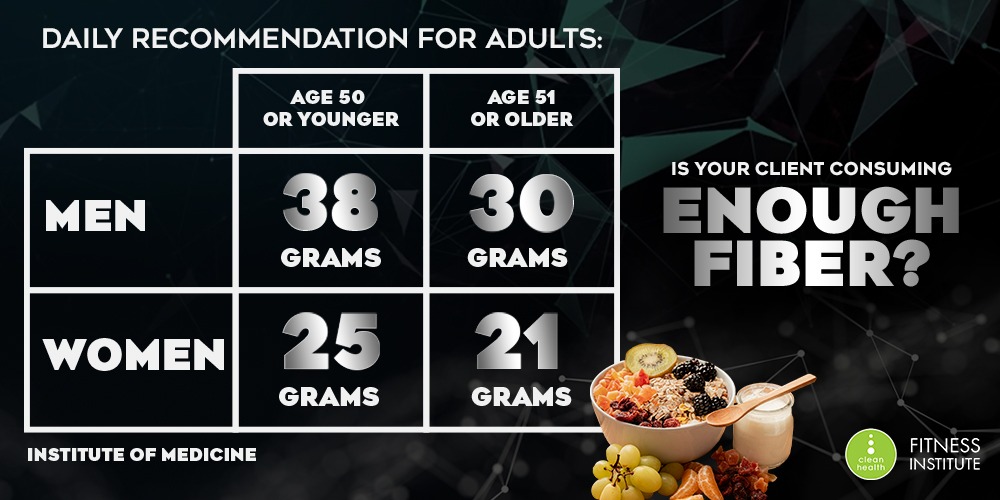

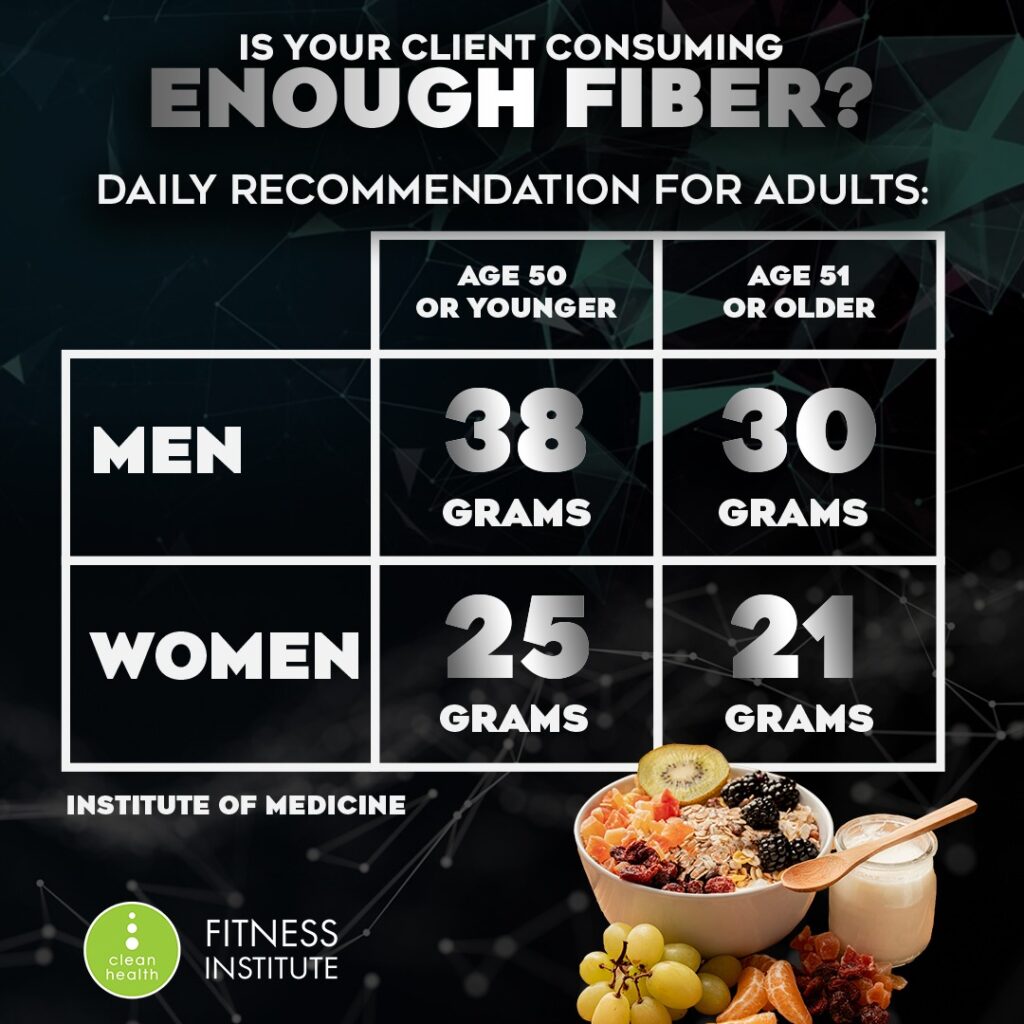

Another reason for not being considered as an essential nutrient is that there is no Estimated Average Requirement or Recommended Dietary Allowance for fiber as there are for other carbohydrate sources. An Adequate Intake (AI) has been established instead, and this amount is contingent on the number of kilocalories consumed (1). The AI for dietary fiber is 14 g total fiber/1,000 kcal, or 25 g for adult women and 38 g for adult men (1,3,14).Fiber categorization is far more complex than we think (5).

Fiber can be categorized as the edible carbohydrate polymers:

- Naturally occurring in foods such as fruits, vegetables, legumes, and cereals.

- Obtained from food raw materials by physical, enzymatic, and chemical means that have a proven physiological benefit; and

- Synthetic carbohydrate polymers with a proven physiological benefit.

Additionally, dietary fibers can be classified according to several parameters, including their primary food source, their chemical structure, their water solubility and viscosity, and their fermentability.

Dietary fibers are classified according to several parameters, including primary food source, chemical structure, water solubility and viscosity, as well as fermentability. Dietary fibers are then subdivided either into polysaccharides (non-starch polysaccharides [NSPs], resistant starch [RS], and resistant oligosaccharides [ROs]) or into insoluble and soluble forms (4).

Most insoluble forms such as cellulose and hemi-cellulose have a faecal bulking effect, as they reach the colon and are not, or only slowly, digested by the gut bacteria, whereas, most soluble fibers do not contribute to faecal bulking, but are fermented by the gut bacteria and thus giving rise to metabolites such as short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs). In contrast to ROs, most soluble NSPs, especially polymers with high molecular weight such as guar gum, certain pectins, β-glucans, and psyllium, are viscous, meaning that they are able to form a gel structure in the intestinal tract that can delay absorption of glucose and lipids influencing post-prandial metabolism (6).

Soluble and insoluble fibers are found in different food sources such as legumes, vegetables, nuts, seeds, fruits, and cereals in different proportions. Soluble fiber is found in oats, peas, beans, apples, citrus fruits, carrots, barley, and psyllium. Insoluble fiber can be found in whole-wheat flour, wheat bran, nuts, beans, and vegetables, such as cauliflower, green beans and potatoes, are good sources of insoluble fiber (6,7).

You may be probably wondering, if fiber is not essential but is kind of essential for the diet, what are the benefits of having a diet high in fiber then?

Here are some of the benefits:

Helps maintaining gut health

A high-fiber diet may lower your risk of developing haemorrhoids and small pouches in your colon (diverticular disease). Studies have also found that a high-fiber diet likely lowers the risk of colorectal cancer. Some fiber is fermented in the colon (15), which interact directly with gut microbes and lead to the production of key metabolites such as short-chain fatty acids that can nourish the colonocytes, help modulating host immune responses (16), but also a potential role in preventing colon diseases(9).

Normalizes bowel movements

Dietary fiber increases the weight and size of your stool and softens it. A bulky stool is easier to pass, decreasing your chance of constipation. If you have loose, watery stools, fiber may help to solidify the stool because it absorbs water and adds bulk to stool (9).

Helps lower cholesterol levels

Soluble fiber found in beans, oats, flaxseed, and oat bran may help lower total blood cholesterol levels by lowering low-density lipoprotein, or “bad,” cholesterol levels. Studies also have shown that high-fiber foods may have other heart-health benefits, such as reducing blood pressure and inflammation (7).

Helps control blood sugar levels

In people with diabetes, fiber — particularly soluble fiber — can slow the absorption of sugar and help improve blood sugar levels. A healthy diet that includes insoluble fiber may also reduce the risk of developing type 2 diabetes (8).

Promotes Longevity

Studies suggest that increasing your dietary fiber intake — especially cereal fiber — is associated with a reduced risk of dying from cardiovascular disease and all cancers (7,8,10).

Improves weight management

High-fiber foods tend to be more filling than low-fiber foods, so you are likely to eat less and stay satisfied longer. And high-fiber foods tend to take longer to eat and to be less “energy dense,” which means they have fewer calories for the same volume of food (11,13). In one study, the intake of guar fiber alone at a dose >5g/serving or its combination with protein (2.6g guar fiber+8g protein/serving) showed acute satiety effects in normal subjects, hence, an ideal natural dietary fiber for use in food and supplement applications at low dosage levels for appetite control (12).

HOW MUCH FIBER DOES YOUR CLIENT NEED?

The AI for dietary fiber is 14 g total fiber/1,000 kcal, or 25 g for adult women and 38 g for adult men.

TIPS FOR FITTING IN MORE FIBER INTO YOUR CLIENT’S DIET

Need ideas for adding more fiber to your client’s meals and snacks? Try these suggestions:

Jump-start the day

For breakfast suggest a high-fiber breakfast cereal — 5 or more grams of fiber a serving. Suggest cereals with “whole grain,” “bran” or “fiber” in the name. Or for them to add a few tablespoons of unprocessed wheat bran, physillium or linseeds to their favourite cereal.

Switch to whole grains

Get your client to consume at least half of all grains as whole grains. Look for breads that list whole wheat, whole-wheat flour or another whole grain as the first ingredient on the label and have at least 2 grams of dietary fiber a serving. Suggest your client to experiment with brown rice, wild rice, barley, whole-wheat pasta, and bulgur wheat.

Bulk up baked goods

Get your client to substitute whole-grain flour for half or all the white flour when baking. Ask them to try adding crushed bran cereal, unprocessed wheat bran or uncooked oatmeal to muffins, cakes, and cookies they make at home.

Lean on legumes

Recommend your clients to add more beans, peas and lentils as they are excellent sources of fiber. Adding kidney beans to canned soup or a green salad can be quite easy and versatile. Or if they are making nachos, tell them to add black beans, lots of fresh veggies, whole-wheat tortilla chips and salsa.

Add more fruit and vegetables

Fruits and vegetables are rich in fiber, as well as vitamins and minerals. Get your client to try eating at least five or more servings daily.

Make snacks count

Fresh fruits, raw vegetables, low-fat popcorn, and whole-grain crackers are all good choices. A handful of nuts or dried fruits also can be a good alternative, high-fiber snack — although be aware that nuts and dried fruits are higher in calories, so make sure these options fit into your client’s daily calorie budget.

Selecting tasty foods that provide fiber is not that difficult. Find out how much dietary fiber your client needs, the foods that contain it, and how to add them to meals and snacks.

TAKEAWAYS:

Fiber isn’t digested by your body; however, it passes relatively intact through your stomach, small intestine and colon and out of your body. Nonetheless, it serves a role throughout its passage, providing a wide range of health benefits short, medium, and long term. Probably best known for its ability to prevent or relieve constipation, weight management, risk reduction of diabetes, heart disease and some types of cancer.

So, is it fiber essential for life? Probably not, is it essential for a healthy diet for proper functioning of the gut? Absolutely!

Want to learn how to create effective and results driven diets for clients from all walks of life? Get The Ultimate Physique Science Bundle by Dr Layne Norton, which includes the Science of Nutrition and Training the Physique Athlete online courses!

Click here to enrol now!

References

1.Codex alimentarius: Dietary Fibre (2009). FAO.orgavailable: http://www.fao.org/tempref/codex/Meetings/CCNFSDU/ccnfsdu26/nf2603ae.pdf

2. Essential nutrient: concept. Available: https://library.med.utah.edu/NetBiochem/nutrition/lect1/2_1.html

3. Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics. Position of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics: Health implications of dietary fiber. J Acad Nutr Diet. 2015;115(11):1861-1870. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S2212267215013866

4. Kassem Makki, et al (2018). The Impact of Dietary Fiber on Gut Microbiota in Host Health and Disease, Cell Host & Microbe. Volume 23, Issue. Available: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chom.2018.05.012

5. L. Ramsden (2004). Grains other than cereals, non-starch polysaccharides. Encyclopedia of Grain Science. Available: https://www.sciencedirect.com/topics/food-science/dietary-fiber

6. E.C. Deehan, et al. (2017), Modulation of the gastrointestinal microbiome with nondigestible fermentable carbohydrates to improve human health. DOI: 10.1128/microbiolspec.BAD-0019-2017

7. Brown L, Rosner B, Willett WW, Sacks FM. Cholesterol-lowering effects of dietary fiber: a meta-analysis. Am J Clin Nutr. 1999;69:30-42.

8. McKeown NM, Meigs JB, Liu S, Wilson PW, Jacques PF. Whole-grain intake is favorably associated with metabolic risk factors for type 2 diabetes and cardiovascular disease in the Framingham Offspring Study. Am J Clin Nutr. 2002;76:390-8.

9. Aldoori WH, Giovannucci EL, Rockett HR, Sampson L, Rimm EB, Willett WC. A prospective study of dietary fiber types and symptomatic diverticular disease in men. J Nutr. 1998;128:714-9.

10. Pereira MA, O’Reilly E, Augustsson K, et al. Dietary fiber and risk of coronary heart disease: a pooled analysis of cohort studies. Arch Intern Med. 2004;164:370-6.

11. Clark MJ, Slavin JL. The effect of fiber on satiety and food intake: a systematic review. J Am Coll Nutr. 2013;32(3):200-211. doi:10.1080/07315724.2013.791194

12. Rao TP. Role of guar fiber in appetite control. Physiol Behav. 2016;164(Pt A):277-283. doi:10.1016/j.physbeh.2016.06.014

13. Paxman JR, Richardson JC, Dettmar PW, Corfe BM. Daily ingestion of alginate reduces energy intake in free-living subjects. Appetite. 2008;51(3):713-719. doi:10.1016/j.appet.2008.06.013

14. Nutrient Reference Values for Australia and New Zealand Including Recommended Dietary Intakes. Available: https://www.nrv.gov.au/sites/default/files/content/n35-dietaryfibre_0.pdf

15. Makki K, Deehan EC, Walter J, Bäckhed F. The Impact of Dietary Fiber on Gut Microbiota in Host Health and Disease. Cell Host Microbe. 2018;23(6):705-715. doi:10.1016/j.chom.2018.05.012

16. Danneskiold-Samsøe NB, Dias de Freitas Queiroz Barros H, Santos R, et al. Interplay between food and gut microbiota in health and disease. Food Res Int. 2019;115:23-31. doi:10.1016/j.foodres.2018.07.043