Written by Astrid Naranjo (Clean Health Accredited Clinical Dietitian)

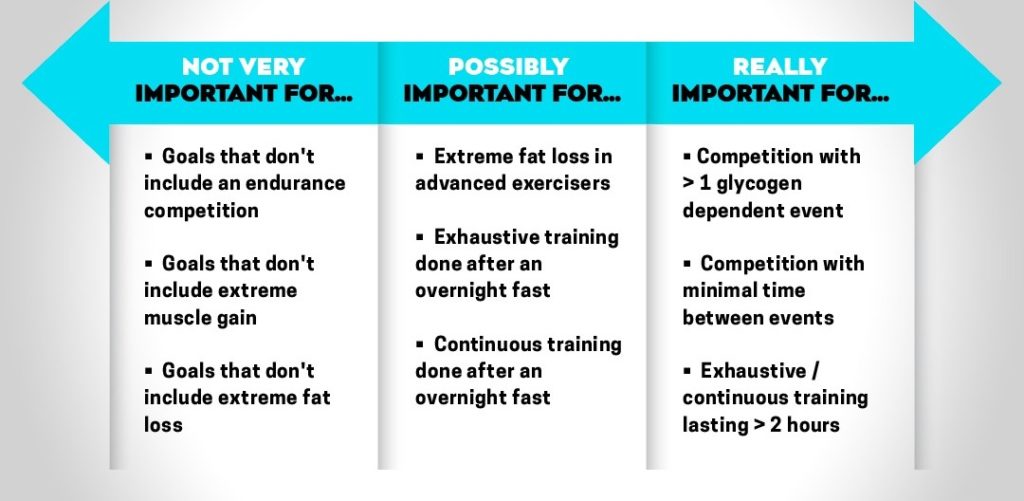

Nutrient timing is a planned alteration of macronutrient intake in order to promote health, workout performance and get/stay lean. Nutrient timing strategies are based on how the body handles different types of food at different times.

Many factors influence energy balance, with the laws of thermodynamics being the most important determinants of weight gain and weight loss. Yes, this means how much the physique athlete eats is still the biggest priority when changing body composition and getting stage lean. Therefore, energy balance here (CICO) still reigns king and it’s what takes priority when considering performance and physical body composition changes for the most part… But nutrient timing can be considered into a plan, the leaner and the closer the athlete gets to show.

Nutrient timing may have some potential effect when it comes to:

- Nutrient partitioning (where the nutrients go when you ingest them)

- Improved body composition

- Improved athletic performance

- Enhanced workout recovery

The emphasis on meal timing started in the early two thousands with a book written by Dr John Ivy called interestingly enough, “Nutrient Timing.” In it, Dr Ivy claimed that nutrient timing was crucial to optimizing performance and body composition. Specifically, he called for feeding during the post workout window in order to optimally trigger anabolism, the famous “anabolic window”.

When it comes down to deciding how to consume carbs and fats? Well, just because there’s no physiological benefit doesn’t mean carb and fat timing couldn’t be use to the client’s advantage (client preference still has a huge role to play here).

Now, a more relevant point to discuss may be whether protein and/or amino acid timing affect LBM maintenance in a physique competitor (1,2). Some studies have consistently shown that ingesting protein/essential amino acids and carbohydrate near or during the training bout can increase muscle protein synthesis (MPS) and suppress muscle protein breakdown (3,4,5). However, there is a disparity between short- and long-term outcomes in studies examining the effect of nutrient timing on resistance training adaptations.

For example, work by Schoenfeld and Aragon suggests a number of weaknesses in the anabolic window hypothesis, showing the tendency for studies supporting the notion of an anabolic window, focusing on untrained individuals or overly specific populations that may not generalize to your typical physique competitor.

At best, the evidence we have says there may be a small benefit to leveraging the anabolic window, but the difference is probably so small that it doesn’t warrant much consideration. If trying to time your meals for the post-workout window causes any risks to your overall daily adherence, then it’s definitely not worth any consideration whatsoever. In fact, there seems to be more evidence pointing that macronutrient totals by the end of the day may be more important than their temporal placement relative to the training bout (1).

More important than timing, nutrient distribution matters a lot more than timing, and this is mostly applicable for protein distribution. Protein is the most important macro as far as body composition outcomes, and even more in physique athletes. Hence, protein intake impacts lean body mass in a pretty direct way. Without adequate protein, the physique competitor wont be able to optimize muscle protein synthesis (7-10).

There’s a little issue with protein though. You see, as important as protein is to building lean tissue, you know the important stuff like organs and muscle, the body has no way to store excess protein. When the body’s in a catabolic state we need to protect muscle, and our best dietary intervention to do this is to ensure sufficient amino acids are already in the blood. Since the body can’t store these amino acids like glucose and fat, ideally we would distribute them in a way to where there’s adequate amino acids available for muscle building throughout the day. That’s because there’s research showing that in terms of muscle protein anabolism, you can’t make up for low protein at one time of the day by over eating at another time of the day due to the anabolic cap from a meal.

That is once you get past a certain level of protein at a meal, probably around 40 to 50 grams, depending on your body weight and the source of protein, you don’t get additional muscle building benefit from additional protein (7-9).

It is recommended for the physique athlete to consume good quality protein (adequate leucine, amounts either with or in the protein source) in a spread & even manner, over three to five meals per day(7-9). Other studies recently suggested, in terms of practical application to resistance training bouts of typical length, a protein dose corresponding with 0.4-0.5 g/kg bodyweight consumed at both the pre- and post-exercise periods (11).

However, for objectives relevant to bodybuilding, the current evidence indicates that the global macronutrient composition of the diet is likely the most important nutritional variable related to chronic training adaptations (1,11).

It is recommended targeting 25 to 50 grams of protein per meal, depending on the protein quality of the source. Hence, frequently consuming a high quality protein meal and regularly be consuming another one soon after, protein intake around training sessions may not be a big of deal.

Now, if the training session is performed first thing in the morning and the athlete doesn’t like to eat before the training session, that can make it more challenging. In a fasted state and amino acid levels in the blood would be at a baseline level. In these cases, it is suggested using an amino acid supplement instead, which may not be a perfect substitute for a complete protein, but at least there will be some level of amino acids in the blood. If the athlete can get a whey protein in or another high quality protein supplement, that may work well too.

Getting the most out of the protein only makes good sense, especially as we get close to the end of competition prep.

Takeaways

What the evidence says about nutrient timing specifically for contest prep?

- Nutrient timing doesn’t seem to have a huge impact. Macronutrient totals by the end of the day may be more important than their temporal placement relative to the training bout . Additionally, evidence indicates that the global macronutrient composition of the diet is likely the most important nutritional variable related to chronic training adaptations. There just isn’t as much quality research on the question of carbohydrate and fat distribution and timing as there is for protein.

- Use carb and fat timing to your clients advantage and increased adherence.

- Protein distribution does matter!

- When the athlete is very lean and calories are low, protein becomes even more important for preserving lean muscle. To help it along we must ensure we’re distributing it over 4 to 6 meals per day and never getting enough leucine in our protein, and that we’re getting 25 to 50 grams of total protein at each sitting.

To learn more about how to specifically tailor, protein, fats and carbs at every stage of your athletes journey, enrol into the Training the Physique Athlete online course! Click here to enrol and save up to 70% off through our extended Cyber Weekend Sale!

References

- Helms, E.R., Aragon, A.A. & Fitschen, P.J. Evidence-based recommendations for natural bodybuilding contest preparation: nutrition and supplementation. J Int Soc Sports Nutr 11, 20 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1186/1550-2783-11-20

- Moore, D. R., Robinson, M. J., Fry, J. L., Tang, J. E., Glover, E. I., Wilkinson, S. B., Prior, T., Tarnopolsky, M. A., & Phillips, S. M. (2009). Ingested protein dose response of muscle and albumin protein synthesis after resistance exercise in young men. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 89(1), 161–168.

- Baty JJ, Hwang H, Ding Z, Bernard JR, Wang B, Kwon B, Ivy JL: The effect of a carbohydrate and protein supplement on resistance exercise performance, hormonal response, and muscle damage. J Strength Cond Res. 2007, 21: 321-329.

- Tipton KD, Elliott TA, Cree MG, Aarsland AA, Sanford AP, Wolfe RR: Stimulation of net muscle protein synthesis by whey protein ingestion before and after exercise. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2007, 292: E71-E76.

- Bird SP, Tarpenning KM, Marino FE: Liquid carbohydrate/essential amino acid ingestion during a short-term bout of resistance exercise suppresses myofibrillar protein degradation. Metabolism. 2006, 55: 570-577. 10.1016/j.metabol.2005.11.011.

- Roberts, B. M., Helms, E. R., Trexler, E. T., & Fitschen, P. J. (2020). Nutritional Recommendations for Physique Athletes. Journal of human kinetics, 71, 79–108. https://doi.org/10.2478/hukin-2019-0096

- Mamerow, M. M., Mettler, J. A., English, K. L., Casperson, S. L., Arentson-Lantz, E., Sheffield-Moore, M., Layman, D. K., & Paddon-Jones, D. (2014). Dietary protein distribution positively influences 24-h muscle protein synthesis in healthy adults. The Journal of Nutrition, 144(6), 876–880.

- Symons, T. B., Sheffield-Moore, M., Wolfe, R. R., & Paddon-Jones, D. (2009). A moderate serving of high-quality protein maximally stimulates skeletal muscle protein synthesis in young and elderly subjects. Journal of the American Dietetic Association, 109(9), 1582–1586.

- Cribb PJ, Hayes A: Effects of supplement timing and resistance exercise on skeletal muscle hypertrophy. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2006, 38: 1918-1925. 10.1249/01.mss.0000233790.08788.3e.

- Burk A, Timpmann S, Medijainen L, Vahi M, Oopik V: Time-divided ingestion pattern of casein-based protein supplement stimulates an increase in fat-free body mass during resistance training in young untrained men. Nutr Res. 2009, 29: 405-413. 10.1016/j.nutres.2009.03.008.

- Aragon AA, Schoenfeld BJ: Nutrient timing revisited: is there a post-exercise anabolic window?. J Int Soc Sports Nutr. 2013, 10: 5-10.1186/1550-2783-10-5.